East Melbourne, Berry Street 039, Servants' Training Institute

- first

- ‹ previous

- 30 of 275

- next ›

- last

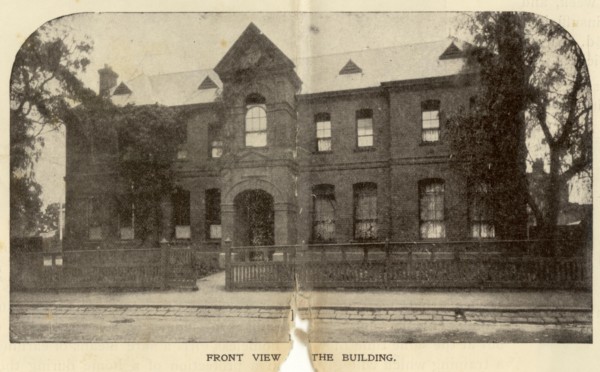

A red brick building of two stories, containing 16 rooms, including two large dormitories and a schoolroom.

On the western side of Berry Street there used to stand a large red brick building known as the Servants’ Training Institute. It came into being when, as the Geelong Advertiser of 21 April 1879 reported:

It has become apparent to the ladies who have visited the industrial school-girls placed in service that an institution for training these girls as domestic servants would be of great advantage. They therefore propose to establish a school for the purpose, to be under the management of a committee of ladies familiar with work of this description. From a circular which we have received we learn that it is intended to begin the school with a number not exceeding 20, to be selected from the Government industrial schools. For these the Government will pay the sum of 5s each weekly, giving the committee power to place them in service. The remainder of the money required for their maintenance must be raised by private subscription. Girls belonging to any Protestant denomination will be eligible for admission to the institution, and will receive a sound moral and religious training. Two hours every day will be devoted to ordinary school instruction, and during the remainder of the working hours the girls will be thoroughly trained in cooking, plain sewing, laundry, and housework.

The 1872 Royal Commission on Industrial and Reformatory Schools condemned the industrial school system for its care of neglected children on several grounds, and in an effort to improve the system children were increasingly placed with foster families, under regular supervision by honorary local Ladies Visiting Committees. It was from amongst these ladies that the committee to establish the Servants’ Training Institute drew its members. Its president was Mrs. Moorhouse, wife of the Bishop of Melbourne, Bishop James Moorhouse.

Initially the Servants’ Training Institute was established in a rented house in The Vaucluse, Richmond, until such time that it received a grant of land on which to construct its own building. The land in Berry Street was granted in 1882 and fund raising began in earnest. Grainger & d’Ebro, architects, were commissioned to draw up plans and their estimated price for a suitable building was £1500 to £2000. Mrs Austin of Barwon Park promised £700 on the condition that another £1400 was raised by the end of the year.

The council was notified on 11 May 1883 that work was about to start and three weeks later the foundation stone was laid in the presence of Bishop Moorhouse. Right on time the building was officially opened on 4 October 1883, Bishop Moorhouse again officiating. It was not completely finished and, at £2500, had already cost more than expected.

The Illustrated News of 28 November 1883 reported that: 'The building consists of two stories … and contains 16 rooms, including two large dormitories and a schoolroom.' The matron’s assistant in the Argus of 17 July 1886 was critical of the building describing it as ‘Gaunt, bare, square, and grim’ ‘with a hard, red front’ and continuing that ‘The architect had surely been inspired with vivid recollections of the English workhouse when he designed anything so unlovely.’ She gave a detailed description of the interior of the building, saying:

The interior of this ugly and workhouse reminding edifice is not very homelike, but it is commodious. To the left of the entrance hall is a long room, schoolroom and dining room combined, for the use of Inmates. Along one side of this room are two rows of desks and forms, fixed to the floor à la mode of the state schools, along the other side the long bare dining table and forms. The kitchen is immediately behind this room, and through a window in the partition wall, the sub matron hands the meals to the hands eager to receive them. A storeroom and a scullery adjoin the kitchen, to the right of the hall are four rooms, two front and two back, with a housemaid’s pantry between them. Two are intended for the matron's use, one is the committee room, and the other is used for mangling and storing linen in. Upstairs we find three dormitories two of them have a few spare beds, and the last one is empty of the inmates it was intended for. Sometimes it is used for hospital purposes. The sub matron’s room, dividing the occupied dormitories, a small bedroom, a clothes room, and the bathroom complete the indoors accommodation. The bathing arrangements are exceedingly neat and convenient, excellent in every way, save that hot water is not provided. The laundry is inconveniently situated, across a damp yard, without shelter overhead when crossing, and consists of washing room and ironing room only. A built-in copper, two troughs, with a wringing machine between them, numerous tubs, two long tables, and an ironing stove comprise the equipment.

According to the same source the girls wore a uniform ‘very becoming to lissom young figures - a 'straight up and down' frock of dark blue serge, snow-white apron and collar, and broad-brimmed hat.' The Illustrated News continued:

There are at present in the institute 28 trainees; of these, 26 have been received from the industrial schools, the Government paying 5s per week each towards the cost of maintenance. The remaining 2 have been placed in the institute by parents who, being unable to look after their children, contribute towards their support whilst they are training. The age at which trainees are received is generally 12 years, but in some cases they have been taken at 10, and the maximum is 15 years, beyond which none are retained. The course of instruction nominally covers three years, but this, in a great measure, naturally depends upon the intelligence and aptitude of the girls, some of whom are fit to take situations long before the expiry of the term named. The instruction is comprehensive and systematic; the girls having their duties changed periodically, so that they go by turn into the kitchen, the laundry, the scullery and all other departments, … Until the girls reach the age of 18 they remain under the supervision of the institute. They are visited by the matron and themselves visit the institute at certain periods, and their wages are deposited in a savings bank and become available to them at the age named, when they are free to do as they please.

For all its good-will and relative success in training girls for domestic service the Institute struggled for survival from the very beginning. It did not attract as many trainees as it hoped, and financial support also fell short of the mark. In 1889 the Chief Secretary threatened it with closure and the land to be handed over to another charitable enterprise. His reasoning was simply that the girls did better in foster care. The committee of course did not want to lose the building they had fought so hard for and decided, in 1890, to broaden the basis of the institution. Most importantly it would take trainees solely from the private sector; it would be non-denominational; girls under 12 would attend nearby Yarra Park State School and an arrangement would be made with the Workingmen’s College to allow girls over state school age to continue their studies where practicable.

However salvation was not to hand and in 1891 the Chief Secretary, Mr Langridge, purchased the site, then described as having been disused for some time, for £2000, with the intention of using if for a police barracks. Yet this never happened and the institution was still struggling on at the end of the year, making a small income taking in laundry.

Things improved and the annual general meeting of 1892 reported an increase in the number of trainees. Ten years later the institute was surviving on a government subsidy, the laundry and subscriptions and donations. In 1902 it was renamed the Training Home for Girls, seen as a less forbidding title and one more appealing to prospective trainees.

The home closed in 1923 when the committee, under president Ada Armytage of Como, resigned. She wrote to the Editor of the Argus on 2 May 1923 explaining their position, ‘when they found that the parents of the girls refused to allow them to enter domestic service, either taking them home, or placing them in factories. As this falsified the name of “Training Home for Girls for Domestic Service,” and was also not in accordance with the terms of the Government grant of the land, we informed the trustees that we did not feel justified in continuing.’ After the war there was less demand for domestic servants and this, no doubt, was the root of the problem.

The trustees initially leased the building to the committee of the Girls’ Friendly Society, which bought it in 1925 and it became known as the School of Homecraft. The Age, 17 April 1925 reported that:-

... the trainees at the school are girls whose parents cannot afford for them to be properly trained in domestic arts. There are no fees whatever for girls who enter the school as trainees, but many of the evening lectures and demonstrations are open to the public at a small fee. There is room at the school, which is situated in Berry-street, East Melbourne for boarders, so that advantage of the tuition can be taken by girls who live a long way from the school.

The house was described as having, been made bright and cheerful;

... with splendid bathrooms and kitchens. The large dormitories upstairs have been fitted as dressing-cubicles, with liberal cupboard and wardrobe accommodation, and the wide verandah is furnished with beds for sleeping out, for the aim of the hostel is that every girl shall enjoy the advantage of sleeping in the open air. The hostel is now ready to accommodate wage earning girls at very moderate rates. There are 20 in residence, and there is accommodation for 28.

In 1935 the building changed hands again and the Mission of St James and St John moved in. It continued as the School of Homecrafts. The trainees came from St Agnes’ Home for Girls in Glenroy, which was founded by the Mission in 1926 to care for girls aged 5 to 14 who were born to unmarried mothers and whose own families could not care for them. Girls 14 to 18 were trained in domestic economy or commercial skills.

The laundry closed in 1939, and the hostel closed in 1976. The building was demolished soon after and the northern half of the land sold to the private sector, on which modern terrace houses have now been built. On the remaining southern section new accommodation was built, which from 1978 to 1991 the Mission of St James and St John ran as Beryl Booth Court. This facility accommodated single parent 'at risk' families for three to six months. Beryl Booth Court was closed in 1991 and the site became the CHOICES Centre for Young Women and their Children. More recently the Alfred Hospital took it over and now runs it under the name Horizon Place, which is a supported accommodation service for people living with HIV.

1883-1902: Servants' Training Institute 1902-1923: Training Home for Girls for Domestic Service (renamed) 1923-1935: Girls' Friendly Society, School of Homecraft 1935-1976: Mission of St James and St John, School of Homecrafts

- first

- ‹ previous

- 30 of 275

- next ›

- last