A terrace of five cottages

The terrace was built house by house over a number of years, presumably as the owner's finances grew. The first two houses to be built were Nos. 8 and 10, and the last was No. 2, which became the owner's own house.

The history section is a series of "books" with a page for each item. You can navigate between pages and books by using the links on the left or at the bottom of each page.

1874 Yarra Park Football

1874 Yarra Park Football

Match

40,000 years ago (or more): First Aborigines arrived in the Yarra area

1802: John Murray sailed into Port Phillip Bay on the Lady Nelson

1803: Lt-Governor David Collins took 460 convicts and white settlers ashore near Sorrento.

1835: Foundation of Melbourne

1839: La Trobe's cottage built in Jolimont, East Melbourne

1853: First private house in East Melbourne, built for Mr Cooke (more)

1858: First game of Australian rules football played at Richmond paddock

1877: First test cricket match between Australia and England played at the MCG.

1891: Yarra River rose 14 metres and destroyed 200 houses in Collingwood and Richmond

1901: Yarra River straightened and Royal Botanic Gardens ornamental lake formed

1954: Proposal to destroy much of East Melbourne for an inner city ring road

1956: Melbourne Olympic Games held at the MCG

1963: La Trobe's cottage relocated to King's Domain

2006: Commonwealth Games held at the MCG

The Journey of Mankind - The Bradshaw Foundation: Tracing the migration of modern humans starting 160,000 years ago

Settlement of Australia - Wikipedia: Genetic, archeological and linguistic sciences point to the single origin of modern mankind

The Pre-History of Australia - Wikipedia: Australia before European settlement

Indigenous Australia - The Australian Museum Online: Chronolgy, culture, stories

Indigenous Australians - Wikipedia: The lives of Australian Aborigines

A Timeline for Aborigines in Victoria - Kooriweb: Major historical events for Aborigines in Victoria

More - National Coordinators of Indigenous Education: More links to Aboriginal history, culture and issues

History of the Yarra River - Yarra River Precinct Association: History of the Yarra River

Yarra River construction works - Federation Square: A place in history

Timeline - Wikipedia: Timeline of Melbourne history

Victoria history - Wikipedia: History of Victoria

Melbourne history - Melbourne Online: Foundation of Melbourne

John Murray - Australian Dictionary of Biography: Murray, John (1775? - 1807?)

John Batman - Australian Dictionary of Biography: Batman, John (1801 - 1839)

William Barak - Australian Dictionary of Biography: Barak, William (1824 - 1903)

East Melbourne - Wikipedia: East Melbourne, Victoria

La Trobe's cottage - Wikipedia: La Trobe's cottage

Yarra Park - Wikipedia: Yarra Park

Victorian Gold Rush - Wikipedia: Victorian gold rush

First Test Cricket Match - Wikipedia: Test cricket history

First Australian Rules Football - Wikipedia: Australian rules football history

1956 Olympic Games - Wikipedia: 1956 Summer Olympics

1956 Olympic Games - IOC: 1956 Olympics

2006 Commonwealth Games - Wikipedia: 2006 Commonwealth Games

This is the collection of building histories written and maintained by the East Melbourne Historical Society.

You can find a particular history by zooming and panning the map. Or you can search the list with the fields below the map.

Using the map

Zoom and pan using the tools at the top left of the map or by dragging and scrolling with your mouse.

Hovering over a marker will show the title of the building history.

Click on a marker to show a summary and a link to the building history page.

The list is sorted by title alphabetically:

Suburb first, then Street name, then Street number.

Restrict the list by entering something in one of the form fields and clicking "Apply".

To return to the complete list clear all form fields and click "Apply".

A terrace of five cottages

The terrace was built house by house over a number of years, presumably as the owner's finances grew. The first two houses to be built were Nos. 8 and 10, and the last was No. 2, which became the owner's own house.

Not known

Initially described in the Rate Books as six rooms, the following year the description changes to five rooms, pantry, bath and shed, and by 1875 it has become seven rooms. The house was built on a wide block with vacant land to the house's south. Fielding lived in the house until 1883 when he sold it to Robert Richardson who added another room.

Cottage

George William Paterson sold his four room cottage very soon after its completion to Andrew Bell who added another room. Bell lived there until at least 1900.

Workshop

First listed in the Rate Books as a workshop but by 1895 the useage had changed to stables. James Peel Browne owned the building until his death in 1905. Sometime after 1910 it became the Commonwealth Motor Garage with Adams and Bradstreet as proprietors.

Cottage

The Notice of Intent to Build gives notice of a cottage to be built by and for Abraham Priest. However the Rate Books from 1870 until at least 1900 give the owner as James Priest. The house is descrbed in 1870 as three rooms, plus a kitchen and servant's room. The following year it is recorded as having six rooms. This description remains the same during the Priests' ownership.

A two storey structure of rustic appearance with half timbered gables and deep verandahs. Its focal point was the octagonal bandstand at the corner of the building.

The Argus, on 28 February 1908, reported:

A block of eighteen flats. Built of brick with a Tudor-Byzantine exterior, with Spanish influence. Decorative brickwork and painted incised render. Art deco interiors

From construction in the 1930s until late 1989 privately owned rental investment residential flats. Nine one bedroom flats; three two bedroom flats; six bed-sitters. Also tower, at that time for communal use. Whole property of eighteen apartments auctioned individually in late 1989, as a company share property - Arbe Questa Nominees. The tower is now privately owned as part of Apt. 18.

Two blocks of 1930's style flats with strong horizontal and vertical accentuation to the facade. They are interesting for their site planning and inward looking outlook to an extensive central garden. The principal building materials are cream brick with tapestry brick, brown brick and render panels. Windows are steel and timber. Notable features include unpainted decorative brickwork. No.

Index to Building Permit Applications dated 25 Oct 1940. First page of Application dated 18 Nov 1940. Letter from Building Surveyor to owners dated 19 Nov 1944 saying 'buildings not yet completed in accordance with specifications approved by this office in as much as fire hoses and chemical extinguishers have not been installed.

A pair of two storey, single fronted houses of brick and stone, now cement rendered

Two four roomed houses were built by William McLean to separately accommodate his father, Peter McLean, and father-in-law, Andrew Arnot. The houses were built on, what was at the time, low-lying floodway land, prior to the construction of the Collingwood railway line in 1901.

Stone house

Originally built as five rooms, a sixth room added in 1882 and a seventh in 1888.

William Niven, stationer, arrived in Melbourne in 1857 on the King of Algeria with his wife, Isabella, and young daughter, also Isabella. He died in 1910.

The houses at 48-50 George Street comprise a pair of semi-detached, nineteenth century, Italianate single-storey residences with basements. The facade is rendered with a moulded cornice and plain parapet extending across both houses. Wing walls have curved parapets and decorative pressed cement corbels. Only the house at No. 48 retains a verandah.

This pair of houses was built in 1861 by and for William Crawford of Melbourne. Nothing further can identify this particular William Crawford with any certainty. The houses, in the Burchett Index of Intents to Build (19 Feb 1861), were described as two 4 room cottages of stone and brick. Crawford named them Bremen Cottages. They were tenanted during Crawford’s ownership.

Two storey double fronted house with simple facade

Abraham Kellet married Ellen Russell in 1857 and was no doubt anxious to provide a home for his new bride and what turned out to be his large brood of children. He advertised for tenders, ‘labour only, for BUILDING four-roomed stone and brick HOUSE’ on 19 October 1860 and he gave notice to Council of his intention to build just ten days later.

Number 55 is a three storey building presenting an asymmetrical facade to the street and exhibiting an understated marriage of Modern and Georgian details in salmon coloured brick. The facade is dominated by a facetted entry rising through the full height of the building with quoins and keystone devices realised in decorative brick around the ground floor entry.

This is part of a cluster of apartment buildings including the neighbouring block at No. 53, and the two blocks at Nos. 29 and 37, as well as the apartments behind in Garden Avenue. All were designed by I.G. Anderson bewteen 1938 and 1941. The area must have been a hive of activity. The building is almost a mirror image of its partner, No.

Pair of two storey brick houses

Not known

A two storey block of flats constructed in 1934 and drawing inspiration from Georgian and Regency sources. Lisieux House is a substantial symmetrical building, its front sections finished in white painted render and surmounted by a roof of terracotta tiles. The street elevation is dominated by a central entrance bay projecting from the otherwise restrained facade.

Built in 1933 by Mansion Constructions, an investment company. The company's directors were politician, Parker Moloney and Anastasia MacIntyre, Moloney's wife's sister. The company was created in 1932, presumably for the purpose of constructing this building.

Large two storey house, with symmetrical facade having central doorway with bay windows each side on ground floor. Brickwork at ground floor level laid in alternating bands of light and dark brick. A tennis court lay to the east of the house.

Maurice Aron owned the house from 1877 to 1897. Maurice Aron of Cohen Aron & Co., was also a partner with Benjamin Josman Fink in an Elizabeth Street emporium called Wallach Bros. Wallach Bros. were furniture manufacturers and retailers. In 1880 NAB lent Fink £60,000 to buy out Aron.

This building is a fine and intact example of 1930's Art Deco flats. Exhibiting extreme care in the detailing including Art Deco treatment of the sash horns on windows ; each flat has a curved balcony with string courses which increase in number up the building.

This block of six two-bedroom flats with six garages was designed by Edith Ingpen in 1933 and built by R & E Seccull Pty Ltd for wealthy bookmaker, Henry Thomas Pamphilon. Ingpen was the first woman to gain an architecture degree from the University of Melbourne and this was her first commission.

A terrace of three two storey houses

Robert R. Rodgers, the first owner, was a sharebroker & land agent of 53 Elizabeth Street, Melbourne

Large two storey house especially noteworthy for its conservative classicism and its unusual verandah with paired cast iron columns

The house was designed in 1865 for William Bowen, a noted Collins Street chemist, by Leonard Terry. Jenkin Collier, noted land boomer, financier and director of the City of Melbourne Bank, owned the property from 1872 to 1918 and occupied it until 1891. It was Collier who added the ballroom in 1886. The house also featured a two storey coach house and stables at the rear.

A photo in 'We of the Never Never with a memoir of Mrs. Gunn by Margaret Berry' shows the house as a large two storey house with a verandah and balcony with cast iron decoration on the west side; and on the east a simple rendered facade with a pair of arched windows above and below. Rate Books describe it as a brick house of twelve rooms.

Mrs. Aeneas Gunn, author of Australian classic, We of the Never Never, occupied the house with her two sisters, Elizabeth Christine Taylor and Carrie Templeton. We of the Never Never with a memoir of Mrs Gunn by Margaret Berry describes the household of "three middle aged very abstemious ladies with a maid". There are photos of the house, and author in the garden.

Three three storey terrace houses of rendered brick. No. 182 retains a timber verandah and balcony at ground and first floor level. Its design and construction are unique. The verandahs and balconies have been removed from Nos. 184 and 186, however No. 184 is currently undergoing restoration and its verandah and balcony will be replaced.

The houses were designed by Joseph Reed who was probably the best known and most prolific architect in nineteenth century Melbourne.

Rate books describe it as a brick house of twelve rooms

This house was designed by Crouch and Wilson for Bernard Marks. Thomas Newton of Charnwood Crescent, St Kilda was the builder. It was completed in 1881. In 1901 Bernard Marks and his family travelled to England and rented the house out. They never returned to the house, moving instead to St Kilda.

Single fronted two story house in the Federation style. The ground floor is red brick, the upper floor is rouch cast plaster.

The house at 190 George Street was built on part of the land once occupied by the original Trinity Church which burnt down on New Year’s Day 1905. The land was sold in 1908 and the new church built on the corner of Clarendon and Hotham Streets.

The 1920s brought many different architectural styles to Melbourne. Tasma fits most closely into the Prairie style with its low-pitched hip roof, wide eaves, strong massing, and restrained use of applied ornamentation. In spite of its two-storey height the building retains a sense of squatness and connection to the ground.

Tasma, 77 Gipps Street was built for Frederick Charles Duncan in 1927. In February the following year he put it on the market when it was advertised as ‘SET of 4 SELF-CONTAINED FLATS, each with 4 rooms, bathroom, S O. New brick 2-storied Building, just completed.’ The purchaser was Joseph Richard Richardson.

Very narrow single fronted two storey house.

This little house was built as an investment for George Milton. The rate books described it as having six rooms on land eleven feet by sixty-six feet. Roughly ninety years later it was deemed uninhabitable by the Housing Commission on grounds of its size and its ruinous condition and a demolition order was issued.

Two storeyed, single fronted house with cast iron balcony, in the style of a terrace house.

The 1870 Rate Books list John Kelly as the owner, and describe the house as having '6 rooms bathroom 2 kitchens servants room and shed'. Thereafter it is listed simply as 8 rooms. In 1873 William Sydney Gibbons appears for the first time as the owner. He lived there with his family until his death in 1917. Gibbons was an analyst, and for many years, the government analyst.

A double fronted shop with residence above. The shop front has been modernised with plate glass windows each side of the central door. There is a modern awning which may have replaced a cast iron verandah. Above there are three arched windows framed by pilasters at each end of the facade. The facade here is painted brick which is possibly polychrome underneath. The side walls are bluestone.

Mr. Webber, the first owner of the building, when he notified the council of his intention to build gave the description 'house', however it appears that the building was used as a shop with residence above from the beginning. It was known then as Webber Bros & Co.

The building faces Ola Cohn Place, with the rear facing Gipps Street. The outline of the original carriageway entrance can still be seen from Ola Cohn Place.

This building was designed as livery stables by the notable architect, Charles d'Ebro in 1888 for William Taylor. In 1938 it was bought by Ola Cohn, the sculptor best known for her Fairies' Tree in the Fitzroy Gardens. She turned it into her home and studio.

A terrace of three two storey houses with cast iron balconies. The cast iron is not original and it is not known whether it has been reproduced from an original sample. The cast iron fences and gates are original.

Samuel Noble Brook (c.1853-1940), first owner and builder of Salisbury Terrace, was variously described as an ornamental ironworker and an importer, however 'it apears that he operated as a self employed building developer for most of his life in business in Melbourne.' [Willingham] On completion of the property Brook sold it to The Standard Mutual Building Society, who within four months had p

A single storey house featuring a wide, low-pitched gable roof. A central, curved bay window sits below. It is made up of five lead-light segments and protected by a window hood. The lower part of the house is unpainted red brick, while the upper part is rendered with rough cast cement. The apex of the gable, above the window hood, is half-timbered.

Andrew Francis Molan owned a hotel and store in Crossley, near Tower Hill in Victoria’s west. Later he moved to Melbourne and bought a hotel in Victoria Parade, Fitzroy. In 1910 his son, Maurice Leslie Molan married, and this seems to have been the stimulus for Andrew to buy the house at 79 Gipps Street. Maurice and his wife, Alice Leona, moved in.

This is an elaborately detailed mock medieval block of flats designed to look like one house, with tuckpointed brick quoins and rough render panels. There is a corbelled brick string course and label mouldings over windows. There is an oriel window to the west facade and fine leadlights to all windows.

These flats are a conversion of an old single storey house. MMBW plans show a small, perhaps four roomed house set well to rear of block, yet there is a small sketch plan in the Building Application file for Clinton Hall which shows a much larger house.

Federation style double-fronted villa with terracotta tile roof and timber verandah.

According to Winston Burchett’s Index to the City of Melbourne’s Notices of Intentions to Build 83 Gipps Street was built 1909-10 for John Loughnan by John Timmins to the design of architects, Crook and Richardson.

A single storey, single fronted house, with a cement rendered 1930s facade. It has a two storey studio at the rear.

George Waterstrom (1829-1907), engineer, owned this house from the time it was built until his death in 1907. He lived in the house until 1873, during which time it is described as two rooms. Extensions were made in 1874 bringing the number of rooms to six, it was extended again in 1878 to arrive at seven rooms. The facade was altered during the 1930s.

The residence at 104 Gipps Street is a two storey rendered Brick townhouse with a refined almost Regency air. It is architecturally significant as a fine and unusual example of a nineteenth century townhouse and is unique for the open work cast iron panels on the verandah columns which although common in Sydney are otherwise unknown in Melbourne.

104 Gipps Street is historically significant for its association with J J Clark, one of Australia's most important architects in the second half of the nineteenth century.

A large two storey cement rendered house in the Italianate style.

Pre-history: Before Crathre House was built there was another house on the site - a large wooden house known as The Bungalow. This house was owned by Henry Dyer as an investment property. He lived next door at 121 Powlett Street with his wife, Mary, and their children. He owned many other properties in the immediate vicinity.

This is a fine two storey ruled render terrace residence with unusual tri-partite verandah. The upper floor verandah has brackets forming semi circular arches supported on timber columns and a concave (hipped) corrugated iron roof. There are render enrichments to the party walls and dentilled eaves. [i-Heritage database]

Builder, Joseph Baxter, built this house for himself to the design of C Langford in 1882. This was in the early days of Clements Langford’s career but he went on to be a master builder working on many of Melbourne’s well-known churches and commercial properties. [see link below].

A terrace of three two storey houses in Regency style. The brick facade is unpainted and there is a timber verandah.

This regency style terrace, with its distinctive timber verandah, was built in 1863 for Henry Dyer, lime and cement merchant, as an investment. Dyer lived with his family around the corner at 121 Powlett Street.

Large red brick house with central carriage way.

Mitchell's four daughters, along with their cousin, Maie Ryan (later Lady Casey) were educated by private governess in Fanecourt's school room. Four of the five became writers. The Mitchell family sold Fanecourt in 1913 and later it was divided into eight flats and renamed Torrington.

Large double fronted, two storey house. Described in 1918 as having "10 rooms 2 bathrooms, 2 maid’s rooms, laundry, large brick motor garage, stabling, man’s room, &c electric light throughout."

The house was built for John Webster in 1869 and designed by architects Reed & Barnes, who designed a number of houses in East Melbourne. Nancy Adams, in her book, Family Fresco,claims the house was once owned by her father, Sir Edward Mitchell, K.C., who named it Stokesay after Stokesay Vicarage in Shropshire where he used to spend university vacations and where the vicar coached him.

A two storey brick house with a pitched slate roof and simple cement rendered facade without verandah or balcony.

The house first appears in the rate books in 1864 and is described as having five rooms. In 1868 it appears as six rooms. Joachimi owned and occupied the house until 1870 when he sold to Daniel B. Pritchard who in turn sold it two years later to R.D. Pitt. Pitt sold to William Woodall in 1882 who was still the owner in 1890.

Single storey, single fronted house with bay window. A second storey has been added to the rear.

In 1865 a three roomed cottage was erected towards the rear of the land. By 1869 the house had doubled in size to six rooms. The addition of a large room at the front brought the house almost to the street and gave it a new asymmetrical appearance. A second storey was added to the rear of the building in 2002. George Milton owned the house until 1922 although he never lived there.

This is an early handmade brick residence of 2 storeys. The facade is simply composed with three bays of exposed brick with a simple brick cornice.

The house was built for the Austrian born, landscape painter, Eugene von Guerard in 1862. It was initially described in the rate books as having four rooms but von Guerard had an additional three rooms built in 1866. James Dickson was the builder. One of the additional rooms was built as the artist's studio.

When owner Leonard Terry put his house on the market it was described in the Argus of 6 July 1872 as, "That spacious and substantially built FAMILY MANSION, containing drawingroom 18ft x 16ft, dining room 18ft x 16ft, schoolroom 27ft x 14ft ; five bedrooms 18ft x 16ft, 18ft x 16ft, 16ft.

Leonard Terry built the house for himself and family. He married twice and had nine children, hence the need for a school room. Matthew Lang, the second owner, appears to have turned this room over to another use. He moved out in 1887, after the death of his son. He continued to own the house until his own death in 1893, and from then until c.1923 it remained in his estate.

One of a row of three, two-storeyed houses, of which No. 165 possesses a porte cochere (i.e. a porch, large enough to accommodate wheeled vehicles). The row is decorated to present a single identity, i.e. the parapet is plain, and unbroken over the three houses and there is a central basket-arched 'entablature' flanked by scrolling. The cornice is dentillated.

Rev. James Caldwell died in 1907 leaving the property to his wife for her lifetime and then to his children. His wife, Mary Anne, died in 1926. The inventory in his will stated that 'Each house is let at 22/6 per week and assessed by the City of Melbourne at £50 per annum. The whole is valued at £2200'

A large two storey house in the Italianate manner

"179 Gipps Street is classified by the National Trust, with the Citation:- 'A fine two-storeyed house in the Italianate manner with delicate stucco detailing and well proportioned openings' It is included in the Register of Historic Buildings established by the Historic Buildings Act 1974 [now Heritage Victoria] 179 seems to have been built in three stages. The first stage in 1861.

Two storey red brick dwelling with terracotta tile roof, leadlight windows and verandah with double ionic columns. There is a clinker brick soldier course , interesting reinforced concrete and wrought iron fence. [City of Melbourne i-Heritage database]

Building work valued at £2,000. Described as ‘attic villa’. Brickwork of ‘Barkly’ bricks. Attic walls to be lined to a height of 3ft. with 3ply Pacific Mahogany. Other woods used: Pacific Maple, Hoop Pine, Jarrah, Oregon. Red gum stumps. Flooring of Baltic White, ‘Dindi’ hardwood.

A double fronted, single storey villa built of polychrome brick. It has a return verandah to the left hand/western side allowing access to the house's main entrance.

42 Gipps Street was built in 1870 for Mrs Anne/Annie Jones by Murray and Hill, a local firm based in Victoria Parade. The firm built many houses in East Melbourne, some for clients, some on its own account.

Block of flats built of clinker brick in an English suburban style.

Arthur Edward Pretty designed the building for the owner Stephen William Gwillam, master builder. An unusual case of the builder choosing the architect rather than the other way around.

A single storey red brick dwelling with tile roof projecting over the timber verandah. There are paired columns on brick plinths with fretwork timber brackets. A bay window projects on the east end. [City of Melbourne i-Heritage database]

Built on part of land previously the site of the Methodist New Connexion Church which was designed by Crouch and Wilson in 1868 and completed in 1869. It was apparently demolished in 1877. The land was subdivided into six building blocks and auctioned in March 1877 and again in September 1878.

A simple two storey tuckpointed brick dwelling with two storey cast iron verandah and render dressings. The parapet has a central cartouche and bracketed cornice. Whilst the entry door has a vermiculated arch over. [City of Melbourne i-Heritage Database]

This house was built in 1884 for Louis Perel by M Gooding & Son of Buckingham Street, Richmond. The earliest rate book entries for it describe it as having six rooms on land 22 by 100 feet. It was built on part of the land on which had once stood the Methodist New Connexion Church, built in 1868. In 1877 the New Connexion Church united with the Weslyans and the church beca

Stories of East Melbourne.

An address to the Historical Society by Marga Macdonald, long time resident of East Melbourne and a founding member of the advisory committee for the new East Melbourne Library and Community Centre.

December 2006

I am really pleased to be here tonight in our beautiful new Community Centre celebrating Xmas with you.

I don't think any of us 6 or so years ago when we started planning for this, thought that we would end up with something quite so large, amazing and so full of character. Since its opening in August you, the historical society and the others, bridge, book group, children corner, garde, etc., have really shown how much East Melbourne needed a focus point, a centre that was our own.

At this point I am going to put in a plug for Elizabeth Cam and her monthly "Friends of the Library" morning tea.

Jill asked me to talk about the library and the site on which we stand. Like most of East Melbourne it has a lot of ghosts attached to it. However, this proved easier said than done and made me realise what an awful lot of history of our area has been lost for evermore and how important you, as a group are to make sure no more gets lost.

However, thank heavens for Winston Burchett who did record quite a lot in the 70's. He has only a snippet about this site and as I tried to find out more I realised why it was so patchy and hard to get - because it aint there!!!

The original house on this site of ours was called East Court and was built about 1857 for Alexander Beatson Balcombe, grandfather of Dame Mabel Brookes. It was a large site going right to Powlett Street. The Balcombes had estates on St. Helena called "The Briars" and Napoleon lived in a pavilion on the estate and became a friend of the family. Alexander Balcombe's father had to leave St Helena as he was suspected of being an intermediary in clandestine correspondence with Paris and after a stint in England he came to Australia. Alexander Balcombe took up land at Mt Martha on the Mornington Peninsula in 1840, built a rough-hewn slab house, the forerunner of what is still there today and open to the public, The Briars is well worth a visit and you could take in Beleura at the same time. The family prospered and Mrs Balcombe moved to East Melbourne sometime in the 1850s, first into a prefabricated house which supposedly originated in India. I suspect she was somewhat more comfortable here than at the Briars. The Balcombes had 2 sons and 5 daughters so a fairly large house was needed and the new house at East Court was built about 1857. Dame Mabel Brookes describes East Court as a hospitable place, where the front door was never closed. The main house stood immediately in front of the prefabricated house, and served as kitchen quarters, and food was transported on trays to the dining room in the main house by a myriad of domestics. It was not uncommon in those days to have the kitchen separate due to the risk of fires in the kitchens. The main house was typically Victorian, huge and stuffy. Lots of silver, antimacassars, carved emus eggs etc. But it did have some of the furniture used by Napoleon on St. Helena, a teak table used by both Wellington and Napoleon, and a writing desk bearing Napoleon's kick marks on the lower panels. I remember once hearing that Dame Mabel was once asked what three things she would take if her house went up in smoke, and she said "jewels, photographs and the death mask of Napoleon. The Briars has some of these relics on display.

Mrs Balcombe was a very outgoing woman, she spent lavishly on charities and, according to her granddaughter had a perennially over drawn account at the bank. She had many friends including a Miss Gibbs, who lived in the house as a companion and Mrs Perry, the Bishop's wife, of Francis Perry House fame amongst other philanthropic works. She was also a friend of Mrs Latrobe, though this must have been before the main house was built in 1857 as Mrs Latrobe went back to Europe in 1854 but the two are supposed to have swapped plants and seeds and the Balcombe and Latrobe children played together. After all it was only a short walk across fields and scrub to the two houses.

In 1839 Superintendent Latrobe, as he then was, later to become Lieutenant Governor, had decided that the conditions in town were unsavoury and selected land in what is now Jolimont, amongst the gum trees. Mrs Latrobe on seeing the area supposedly said "Au Jolie Mont", and so it remains. The Latrobe house was also a prefab, imported from England in two parts. Mrs Latrobe was a keen gardener and it must have looked lovely with its flower gardens and overlooking where the Botanical gardens now are. There is a wonderful picture of the house and garden in the State Library with two ladies conversing under an arbour. I'm sure you all know the sad history of the Latrobe house, how it fell into disrepair, was in the Bedggood Shoe factory grounds and was removed in 1960 to its current position in the Domain. Not visited very often but well worth a visit. I'm told that the Latrobe's had a holiday house at Queenscliff. I haven't been able to find out where but somewhere on the cliff, which must be where the fort is now. Prime real estate. Mrs Latrobe, who9 was Swiss herself, encouraged and organised Swiss vignerons to plant the first vineyards in the Barrabool hills. They were unfortunately wiped out by the Phylloxera scourge of the 1870's. Mrs Latrobe, not in good health, went back to Switzerland, her home of birth, and died there in 1854.

A monument to Mrs Latrobe was on the wall in the Cairns Memorial Church, now the Cairns apartments, and told the story of "Oh Jolie Mont!" The Cairns Church was another interesting place, which went up in great sheets of flame in 1988. The church was built in 1883 by Twentyman and Askew and was a centre of Presbyterianism. My sister-in-law, who was a boarder at P.L.C. when it was in E. Melbourne, remembers walking in a crocodile to church, hats and gloves at the ready. There were wonderful memorials on the wall to sea-farers and other old timers, it had a very small congregation in the 70's 80's but it had a wonderful basement. It was where we went to vote, all sorts of groups had meetings there, the Highland dancers, the stamp and coin collectors the train society, and, I remember, the Love Bird Society! We took our children and a couple of cousins who were staying with us there one Sunday when we first arrived in East Melbourne And the verger rubbed his hands with glee and announced, "Now we can start the Sunday School again!" The children refused to go back! The inferno was so great when it went up in flames and not one record was saved.

But back to this site. Mrs Balcombe died in 1907 and East court had two owners in fairly quick succession. It had a series of owners over the next 60 years, and its fortune waxed and waned as did East Melbourne. It's name was changed at some stage to Lanivet and its last private owner appears to have been a Miss White who was there for about 15 years . Cido, our librarian, told me that a lady he spoke to one day told him that she remembers as a child "The Ghost House" which had an overgrown garden and had an old lady living there. The only thing I can find out about Lanivet is of a small town in Cornwall of that name so can only assume that one of the owners had some connection there. The East Melbourne Library was then opened there on 29th May 1964.

The little old cream brick library served us well for many years but as East Melbourne changed so did the needs of the people and time and technology caught up with it. We moved into East Melbourne in 1971 and lived directly behind the library, and the children used to climb over the back fence to get there. One time my young daughter nearly spent the night there as the Library shut and she was left unnoticed reading in a beanbag, fortunately seen by the Librarian banging on the window as she was driving out!! It was a friendly little place but we outgrew it and we still didn't have a centre for community activities.

In the 1990 there was talk of the Melbourne City Council getting rid of our library, amalgamating us with Richmond or Fitzroy, and selling off the land. We think a developer must have been in the wings!!! There was also talk of a central city library and we could use that. There were library meetings of local residents to campaign not to close but then the Council changed tactics and asked the East Melbourne Group to get involved. I was a member of the East Melbourne Group Committee at that time and Nerida Samson, our worthy president, asked me to take on the Library Advisory Group, as it was then called. We organised a public meeting, to which about 20 people came, formed a committee of locals Irene de Lautour, Frank and Penny Lewis, Fiona Wood, Peter Moon and myself. We had one particularly helpful member of the Council, Maurice Bellamy, who was our liaison with the rest of Council, They provided the money for a professional postal survey, which some of you may remember, so that we could find out what it was that the suburb really wanted. It came out overwhelmingly that an enlarged library was wanted and an area where people could meet socially and for group activities. The Council then totally came out supporting us and money was set aside in the budget for a new building. We had many, many meetings with all the players, the Yarra Melbourne library bosses and our own library staff who were always most helpful, the various local groups, yourselves included, the Council who allocated the money in their budget, town planners, architects etc., and it finally all happened. There were several changes of plans. I remember at one stage there was a rather strange conveyor belt to the children's area, which had to go. We had to deal with complaints, of which there were not many actually. The proposed café was a source of contention and had to go which was a pity but in the end we got there.

The East Melbourne Group with first of all Nerida, and later, Margaret Wood as President, supported us in all our efforts. Irene de Lautour and myself left the Committee after about 15 months and left the others to do the rest of it, with Peter, and later Frank, as their Captain. And the result - what we have today!

I know there are problems, things that niggle and aren't quite right; the air-conditioning, the catering facilities to name but two. Rob Adams, the principal Architect is away overseas till January and has promised to look into it all on his return. I built a house at Queenscliff which was finished last February and the builder and I are still working on bits so it takes time. In the meantime we, East Melbourne, have a wonderful facility of which we can be justly proud.

Enjoy it!

HAPPY CHRISTMAS!!!

When Charles Joseph La Trobe arrived in Melbourne in 1839 as the newly appointed superintendent of the colony of Port Phillip he would have found the north bank of the Yarra, just east of the city, to be bordered by swamps and lagoons rising gently to open scrubland dominated by large river red gums. He would have seen aborigines from the local Wurundjeri clan hunting and fishing in the lagoons; and occasionally he might have seen a corroborree as neighbouring clans joined them in celebration.

He immediately recognised the potential of the area for recreational use and proposed that approximately 240 acres stretching, in modern terms, from Punt Road to Princes Bridge, and northwards to Wellington Parade and Flinders Street, be reserved for that purpose. However it was not until 1873 that this visionary proposal was ratified by an Act of Parliament. By then the original 240 acres had suffered several excisions.

La Trobe, himself, made the first cut when he bought his Jolimont land in 1840. Next, in 1853, the Melbourne Cricket Ground was given permissive occupancy of nine acres which was formally recognised as a Crown Grant in 1867.

1866 Richmond Paddock

1866 Richmond Paddock

Australian football matchIn 1858 the first game of Australian Rules Football was played in Richmond Paddock, or Yarra Park, between Scotch College and Melbourne Gammar. However it was many years before the game was allowed to be played at the MCG as its turf was considered too delicate for the rough and tumble of the new game.

A stand built at the MCG in 1876 was reversible which could be made to face the MCG in summer for cricket, or the Richmond Paddock in winter for football. It burnt down in 1884.

In 1859 the railway line to Richmond effectively cut the park in half lengthways. In the same year land was reserved for the Swan Street extension, although it was not built until 1875. Thirty three acres to the south of this was given to the Acclimatisation Society which gave way to the Friendly Society Gardens when the animals were moved to Royal Park two years later as the start of the Zoo. Now that area is Olympic Park.

The Acclimatisation Society was linked to the Botanical Gardens by a foot bridge over the Yarra, and passengers on the Richmond line were once able to alight at the Botanical Gardens Railway Station, and from there it was just a short walk to either destination. The old railway bridge in Yarra Park, although much lengthened now, is a relic of those days. The land on the corner of Punt Road and Wellington Parade, which had once been the police barracks and gaol, was also excluded from the grant. A section of it was granted separately for a state school. The remainder was subdivided into 83 residential allotments and sold in 1881.

The remaining land when it was finally reserved in 1873 was gazetted as two parks, one each side of Jolimont Road, which then ran to the river and Branders’ ferry. Flinders Park was to the west, replacing the Police Magistrate’s Paddock where Captain Lonsdale had built his cottage; and Yarra Park to the east, replacing the old Police, or Government, Paddock, also known as the Richmond Paddock, where the police horses had once grazed. Yarra Park also included the parcel of land to the south of Swan Street known as Gosch’s Paddock.

Modern encroachments have reduced the size of the park even further. The MCG’s girth has expanded considerably. And the tennis centre, or Melbourne Park, once called Flinders Park because that is where it was, has slipped into Yarra Park with the building of the Vodaphone Arena in 2000.

The 1956 Olympic Games marked the beginning of Yarra Park’s degradation. This was the first time visitors to the MCG had been allowed to park their cars in the park proper. Previously parking had been limited to the corner formed by Brunton Avenue and Jolimont Street. The Council was very pleased with this clever solution and has never looked back, and except, ironically, for the hugely successful banning of car parking during the 2006 Commonwealth Games, cars now fill Yarra Park every time the MCG is used. The result is bare, compacted earth and suffering trees; a far cry from the thriving natural environment La Trobe hoped to bequeath to the citizens of Melbourne for their recreation and pleasure.

We would love to publish more stories about the residents of East Melbourne. If you have a historical record, an obituary, a memoir, an oral history, letters or a personal glimpse and would like to share it please make contact.

Bitter Honeymoon front coverMelbourne author Jean Campbell (1901-1984) was the writer of five novels for William Hutchinson, publishers, in London, and also produced magazine style romance novels for New Century Press, 3 North York St., Sydney. These booklets, sold for 4d, were distributed through newsagents and booksellers and boasted "A new title every month." So, while the novels were serious writing, Bitter Honeymoon, Passion from Peking and Her Fate in the Stars were clearly produced for light reading, though given the continuing popularity of Mills and Boon even today, may well have made their author a good deal of money. Many were published during World War 2. On the back page of Passion from Peking is an inscription: "This book has been reduced in pages to reflect the War Time Economy".

Bitter Honeymoon front coverMelbourne author Jean Campbell (1901-1984) was the writer of five novels for William Hutchinson, publishers, in London, and also produced magazine style romance novels for New Century Press, 3 North York St., Sydney. These booklets, sold for 4d, were distributed through newsagents and booksellers and boasted "A new title every month." So, while the novels were serious writing, Bitter Honeymoon, Passion from Peking and Her Fate in the Stars were clearly produced for light reading, though given the continuing popularity of Mills and Boon even today, may well have made their author a good deal of money. Many were published during World War 2. On the back page of Passion from Peking is an inscription: "This book has been reduced in pages to reflect the War Time Economy".

Jean Campbell lived in East Melbourne and was clearly a member of a literary/artistic set. Her portrait, by Lina Bryans, hangs in the National Gallery at Federation Square. Titled "The Babe is Wise", from the title of one of her most popular books. It shows a young, fashionably dressed woman who exudes independence and self assurance. The State Library has a photographic portrait of her by Wolfgang Sievers, better known for his architectural photos, especially of the ICI building. There is a third, autographed photograph held in the National Gallery of Canberra, described as "prepared for a luncheon given by Hutchinson representative George Sutton when Brass and Cymbals was published". Hutchinsons obviously saw her as a promising author and were prepared to spend to promote her image.

But where did she live in East Melbourne? The Sievers photograph, dated 1950, catches her in her East Melbourne flat, and the electoral roll has her living at 17 Powlett Street at that time. However this flat, tucked behind the house at that address, was quite small – a single bedroom, with bathroom attached, a small kitchen and sitting room – somewhere perhaps she moved to in her later years.

Clues may, perhaps, be found in her work. One of her greatest strengths as a writer was in the detail of landscapes and buildings that she described. She loved Melbourne, it is clear, and at least two of her novels are set there. East Melbourne, with its "curiously mixed charm" features strongly in The Babe is Wise and she writes that from the house "you could look across to the city, and in the evenings, when the electric signs sprang into life, it was rich, not gaudy with colour." This could be either Jolimont or East Melbourne proper, but another passage fixes her location clearly in Jolimont:

Then there was the other entrancing aspect of the locality. If it hadn't been for the electric trains and trams thundering by at intervals … you might have thought you were living in a sylvan retreat … there were the gardens over the way and the park at the back … and a bridge over the Yarra that brought you to some more gardens, the Botanical.

So where did she live? The description of the cottage in the novel is quite specific:

She saw it for the first time cuddling in between two tall old brick houses for all the world like a small fat child toddling out between a couple of maiden aunts. She was certain that it must have been the identical cottage made by the witch to lure Hansel and Gretel.

157 Wellington Parade South, Jolimont: Could this be Jean Campbell's house?Perhaps it wasn't her house at all, but that of a friend whom she visited often, because she describes the inside of the cottage and the layout of the rooms quite specifically. But there is something so personal about her knowledge, so loving, that she seems to be describing a house in which she lived.

157 Wellington Parade South, Jolimont: Could this be Jean Campbell's house?Perhaps it wasn't her house at all, but that of a friend whom she visited often, because she describes the inside of the cottage and the layout of the rooms quite specifically. But there is something so personal about her knowledge, so loving, that she seems to be describing a house in which she lived.

Can any of our readers help us with information about Jean Campbell or about the house in which she lived? And if any of our members is visiting Canberra and has some free time, perhaps he or she could look through the collection of Jean Campbell"s papers held there and help us in our quest.

James McArdle has contacted us to tell us that in 1975 Paul Cox and Prahran College students, including himself, made a film about Jean Campbell and her day-to-day life in her retirement home in Windsor. It was called 'We're All Alone My Dear'. James adds that she was, 'still feisty and reasonably fit. My input was to film her through the front door of the home and then walking in the nearby Victoria Gardens. It was clear she was frustrated with the other inhabitants as a poor match for her intellect.' There is a copy of the film at ACMI.

See also, Victorian's Book Accepted: https://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article203812827

James McArdle, email 7 May 2025

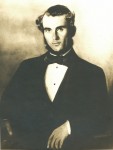

Cooke, HenryHenry Cooke was born on 10 March 1818 at Egglestone Abbey Paper Mill in Durham, England, fourth child of Henry and Hannah (nee Wilkinson). He was baptised two weeks later in Startforth Church, the day after his mother died. His father remarried in 1819 and fathered fifteen children, four with his first and eleven with his second wife. Henry and his siblings are descended from a long line of Papermakers in Durham and Yorkshire.

Cooke, HenryHenry Cooke was born on 10 March 1818 at Egglestone Abbey Paper Mill in Durham, England, fourth child of Henry and Hannah (nee Wilkinson). He was baptised two weeks later in Startforth Church, the day after his mother died. His father remarried in 1819 and fathered fifteen children, four with his first and eleven with his second wife. Henry and his siblings are descended from a long line of Papermakers in Durham and Yorkshire.

The family moved to “Howe Villa” Richmond, Yorkshire, eighteen miles away when Henry was twelve years old. While there, Henry worked as a Papermaker at the Whitcliffe Mill run by the family, until leaving England with his brother John in 1842, for Nelson, New Zealand. Henry and John spent about three years there, as landowners and early settlers before moving across to Victoria, Australia and continuing with landholdings north west of Melbourne, running cattle and sheep. Over the years they bought and sold land together in East Melbourne, Yan Yean and Mulgrave.

Henry and John were some of the first landowners in East Melbourne, importing timber from New Zealand to build residences in 1852. Henry lived in East Melbourne for many years with his wife Amelia and their young family. His home named “Egglestone Villa” at 180 Clarendon St was the first private residence in East Melbourne, and he lived there for about three years. This is now the site of the Freemasons Hospital. From 1856 to 1859 Henry was farming near Geelong, but he returned to East Melbourne and lived there for at least two years in Grey St and at 197 Albert St, before moving to “Howe Villa” at Yarra Falls from 1863 to1866. The family returned to live in East Melbourne in the1870’s, and lived in Jolimont Square and then at 102 Hotham St, for over fifteen years.

Henry and his brother John set up a general merchant business in 1851, initially operating in Sydney, Ballarat and Melbourne. During the Victorian Gold Rush they received gold on consignment for safekeeping. The merchant business continued in Melbourne on the corner of Bond and Flinders St until the late 1870’s, when it was moved to Swanston St. The focus of the business in these later years seems to have been on the importing and sale of paper products, including books, religious tracts and paperhangings.

In 1854 Henry and John founded “The Age” newspaper in Melbourne, partly because they disagreed with the way the existing papers were dealing with issues of the times. The Cooke brothers had been brought up in the paper mill industry, which possibly explains why they undertook this venture. Within three months they were struggling for finance and relinquished ownership, but the paper went on to celebrate over one hundred and fifty years in operation. John returned to the family paper mill in Yorkshire at about the time another brother, Francis arrived in Melbourne, and Francis then worked with Henry in the merchant business before he migrated to New Zealand in 1859. It appears that the brothers stayed in business together, as importers and merchants.

During the 1850’s Henry was elected as a Melbourne City councillor and was also a Director of the Hobsons Bay Railway Company. He resigned from the company when they wanted to run trains on Sundays, which as a fervent Methodist he strongly objected to.  Ham, Amelia Annie JobSimilarly, during his time as owner of “The Age”, he would not allow any work to be done on the paper on Sundays. Henry was a church trustee, class leader and superintendent of the Sunday school of the Methodist Church in Lonsdale St. In his later years he also spent his Sundays as a lay preacher and distributed religious tracts to the needy and those in prison watch houses. He was also clearly a family man with strong links to his extended family in England. Several of his properties in Victoria were named after his childhood homes.

Ham, Amelia Annie JobSimilarly, during his time as owner of “The Age”, he would not allow any work to be done on the paper on Sundays. Henry was a church trustee, class leader and superintendent of the Sunday school of the Methodist Church in Lonsdale St. In his later years he also spent his Sundays as a lay preacher and distributed religious tracts to the needy and those in prison watch houses. He was also clearly a family man with strong links to his extended family in England. Several of his properties in Victoria were named after his childhood homes.

On 5 Aug 1851 in Sydney, Henry married Amelia Annie Job Ham, daughter of Rev John Ham, the first Baptist Minister in Melbourne, and they had twelve children. Henry died on 18 Mar 1889 at his home “Egglestone” Dandenong Rd, in Oakleigh and is buried in the Cooke family grave in Melbourne General Cemetery.

By Jane Morey (great great grand-daughter), 25 June 2008

Thomas Joshua Jackson was born in Dublin, Ireland in 1834, and emigrated to Victoria around 1852, but little is known of these early years of his life. Research in Ireland has revealed little, other than he was probably an only son. His life from 1852 was inextricably mixed together with those of his aunt's families. Jackson's aunt Sarah Heaton married in Ireland for the second time at the age of 40, to Henry Young, a law clerk. The Youngs had one child, H. F. Young, in 1845, and emigrated to Victoria in 1849, with three children. These were five year old H. F. Young and the two youngest children from Sarah Young's first marriage - 13 year old John Connell and nine year old and only daughter Sarah Isabella Connell. Cooper, J.B., The History of St Kilda: From Its First Settlement to a City and After, 1840, 1930, v.1., Printers Proprietary Limited, Melbourne, 1931, p.162. Sarah Young's eldest son also appears to have arrived separately in Victoria about 1851. By 1859, Henry Young senior had become the landlord of the Elsternwick Hotel, one of the earliest 'suburban' hotels in Melbourne. The Australian Brewers' Journal, 20 November 1919, p.81.

Between 1852 and 1861 nothing concrete is recorded about Jackson. H. F. Young later said that in 1861 he had 'chummed together' with Jackson, and 'set forth for New Zealand, where for some considerable time they successfully engaged in mining. This might imply that Jackson had some previous experience of mining, perhaps on the Victorian gold fields; it is Thomas Jackson's name which appears as a preferred claim holder at Gabriel's Gully in Otago province in early 1862. Cole, R.K., Harmston, G., and Telow, E. (contributors.), R. K. Cole collection of hotel records/ surname records, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, 2000, vA, p.339. The third Maori War of 1863 and declining gold returns by 1864 probably acted as catalysts for a return to Melbourne. The next clear public reference to Jackson occurs in December 1867, when he appears in a high profile and somewhat amusing court case involving Young senior.

The town clerk of Melbourne, Edmund Gerald FitzGibbon Barrett, B., 'FitzGibbon, Edmund Gerald (1825 - 1905)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vA, Melbourne University Press, 1972, pp.181-182., had stopped at the Elsternwick Hotel on his way to Melbourne from Mt. Eliza, and remaining on his horse outside, called for a beer. Finding himself ignored, he then rode his horse into the bar to claim a drink first hand. Young senior, the landlord, 'assisted by a man named Thomas Jackson', promptly evicted him from the bar. Cross-summons ensued. Young initially claimed FitzGibbon was drunk, while FitzGibbon claimed the horse, due to a fondness for Colonial ale, rode him into the bar. The judge decided for the horse and Young had to pay £50 and costs. Other charges, including against Jackson, and FitzGibbon by Young, were dismissed. The Argus, 16th January 1867, p.5 and 5th April, 1867, p.5.

Soon after this court case, Jackson entered business together with H.F. Young when they took up a licence for Sparrow's Hotel at St. Kilda junction, first recorded in 1868. Cole, R.K., Harmston, G., and Telow, E. (contributors.), R. K. Cole collection of hotel records/ surname records, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, 2000, vA, p.339. By then Melbourne was on the cusp of a decade long financial, industrial and property boom. Jackson and Young positioned themselves perfectly for it when in 1875 they made their move across the Yarra River to the Prince's Bridge Hotel. The Princes' Bridge Hotel was established there in July 1861. Schumer, L.A., Princes Bridge Hotel Young and Jackson's, East Malvern, 1981, pA. With license and lease in hand, they promptly made their mark with extensive renovations. The Young and Jackson names and management of the hotel became so well known that it began to be referred to as 'Young and Jackson's'. The words 'Young and Jackson' did not appear on the hotel facade until many years after they first won the licence; it would have been more convenient to retain the licence in the old name. The partnership seems to have been based on a 'gentleman's agreement'. Young, who continued to be associated with the hotel until 1914, ensured the fame of the hotel through astute marketing, including with the purchase of the then controversial Chloe painting in 1909.

In August 1878, Jackson finally married, at 44. His bride was a widow, well known to Jackson; in fact she was his first cousin. Sarah Isabella Cavanagh was the only daughter of Sarah Young's first marriage in Ireland. Her late husband, Michael Cavanagh, protege of Henry Young senior and former landlord of the Prince of Wales Hotel in Prahran, had died in 1877. He apparently left no will or property. Sarah Young died in February 1883. Sarah Cavanagh brought into the marriage with Jackson her 16 year old son, James. Until the time of his marriage, Jackson most likely had lived at the Elsternwick, Sparrow's and the Princes Bridge Hotels in turn. Once married, there was an imperative to find a place of his own and by 1879 Jackson had taken up land in Jolimont Road, East Melbourne, 'a most attractive proposition for the investor.' Burchett, W., East Melbourne Walkabout, Cypress Books, Melbourne, 1975, p.9.

In 1880, the year that Irish-Australian bushranger Ned Kelly went to the gallows, the Young and Jackson partnership was extended once again with a renewed lease on the Prince's Bridge Hotel, this time for 14 years at an annual rent of £1,000, which included the adjoining building in Flinders Street. New connections to Flinders Street station in 1879 had quickly boosted confidence in rail travel and the popularity of Flinders Street Station for train riders from country and city alike. The hotel was in the right place at the right time and well positioned for the coming boom. It seemed that the incredible decade of growth in Melbourne from 1880-1890 would never end; the crash and recession which followed was of equally monumental proportions. The crash had its effect even on popular and profitable hotels and may have precipitated the end of the partnership of Young and Jackson. After all, by 1894, Jackson had turned 60, with plenty of business to engage him and property development as well.

Jackson's name first appears in connection with Jolimont Road in the Sands and McDougall Directory and in the Melbourne City Council Rate Books in 1879. Jackson also appears in Albert Ward in the 1878/1879 List of Citizens, a Melbourne City Council record. In August 1879, he applied to bring some vacant land on Jolimont Road under the Transfer of Land Statute, and acquired other property on the street. By 1881, he was living in one of three six bedroom brick houses that he then owned. Over the years to his death in 1900, Jackson appears to have owned between two and five blocks, with a double block making up his eventual home on Jolimont Road, at Number 42. Much of the research on Jackson's land and house interests on Jolimont Road was completed by Peter Fielding 1998-2001. For the List of Citizens, see PROV, VPRS 4029/P3. For the 1879 notice, see The Argus, 26th August 1879, p.8.

Jackson was there in August 1881 when the railway level crossing for the line from Brighton to Flinders Street not far from his home became the scene of one of Melbourne's great rail disasters. Loaded with some of the business elite of Brighton and Elsternwick, as well as ordinary passengers including a coach especially for schoolgirls, the 9 a.m. Brighton Express, three minutes from Flinders Street, went over an embankment and smashed up, killing three passengers outright (a fourth died later) and injuring dozens. The Argus tells the story:

At this stage - it was but a few minutes after the accident - the people around began to realise how matters stood, and the cry was for pickaxes, axes and levers. Speedily the already roused inhabitants of Jolimont were requisitioned for the necessary implements, and a dozen or so of axes appeared upon the scene. They were mostly obtained through the personal exertions of Mr. T.J. Jackson, who also thoughtfully sent a supply of brandy with jugs of water to revive the fainting.' The Argus, 31 st August 1881, pp.5-6.

In December 1882, Jackson's architect, James Gall, placed an advertisement in the newspapers calling for tenders to erect a 'villa residence' for Jackson. A Notice to Build was lodged in January 1883. The Argus, 1st December 1882, p.3 and PROV, VPRS 9463/P3, Notice of Intention to Build, No.134. Jackson called the house' Eblana', the Latin spelling for Dublin his city of birth. It became a comfortable two storey home, complete with tiled balcony and hall, vaulted timber ceilings, lead light windows and horse stables in the rear giving access to Jolimont Lane. Jackson with a year added a single storey extension on the ajoining block in which he installed a billiard table.* Years after, it was described by unknowing but ever optimistic real estate agents as a 'ballroom'. Across the street between Jolimont Road and the City lay the East Melbourne Cricket Ground (later an early home of the Essendon Football Club) which

... saw many famous sporting events including in March 1887, a match between Australia and England when the two elevens were shuffled and divided into teams of smokers and non-smokers. Five years later, Dr. Grace led an English team against the East Melbourne Cricket Club on this ground. Burchett, W., East Melbourne Walkabout, Cypress Books, Melbourne, 1975, p.14.

Jackson's records in 1901 give a fascinating insight into life at Eblana and the labour intensive consumerism at the turn of the 20th century. The list of personal liabilities includes bills from doctor, chemist, bell repairer, pork butcher (the area had a large Jewish community at the time and so pork was sold separately), butcher, baker, butterman, wood, dairy milkman, Chinese greengrocer, servant, gardener, washerwoman, fruiterer, fishmonger, nurse, wine and brandy supplies (from H.F. Young), house repairs, eggs and boot makers. PROV, VPRS 28/P3, Probate Jurisdiction Sarah Isabella Jackson 1924. Most of these services provided personalised service to Jackson's home at Jolimont Street. He also paid separately for street lighting and sewage services, in addition to his rates. Most home owners in Melbourne today would be envious of the fact that in 1900, Jackson only paid £29/3/4 in income tax. That he and Sarah Jackson lived such a comfortable life was evidence of the financial security he had achieved from his hotel businesses and business investments. PROV, VPRS 28/P2, Probate Thomas Joshua Jackson 1901 (Probate Jurisdiction).

Exactly when Jackson began making business investments is not known with certainty. The opening of the Melbourne Stock Exchange in 1884 may have provided an early incentive. Both Jackson and H. F. Young invested in a diverse range of business, banks, a brewery, brickworks, gold mines and government stocks, as well as property and in speculative new technology opportunities. Young was an astute businessman who went on to develop a highly valued business portfolio and art collection which was valued at over £120,000 by the time of his death in 1925. PROV, VPRS28/P3/1604 and VPRS7591/P2/725, Will and Probate Henry Figsby Young 1923.

Jackson, although not as successful as Young in business and died some 25 years before Young, still retired from the hotel with a comfortable income from his portfolio of interests. Most of Jackson's investments did well, even during the major recession of 1891-1895. But in common with today's investors, not all the tips he received worked out for him. In the attendant bank crashes to the recession, Jackson also lost like many others. The Metropolitan Bank failed in 1892; Jackson and two of his wife's relatives were listed as depositors in The Argus in March 1892 when a meeting at the Athenaeum Upper-hall was called 'to arrange for their representation in the liquidation of the bank.' The Argus, 2nd March 1892, p.8. The fact that only a handful of depositors were named in the public notice suggested that they had considerable sums on deposit. The Montgomeries Brewing Company was another investment which turned sour.

Both Jackson and H.F. Young invested their reputations and perhaps capital when Montgomeries Brewing Company was formed in 1888. The Argus, 24th February 1888, p.9. The new limited liability company floated on 1st March 1888 with 240,000 shares at £1/10- each. The directors included Jackson, and H.F. Young at a later date, while stockholders meetings were often held at the Young and Jackson Hotel. By 1897, Montgomeries finally failed, and went under owing the Bank of Australasia £73,302. Disgruntled investors sued the directors including Jackson but not Young who by this time had astutely managed to divest.

The case came to the Victorian Supreme Court in 1899 and began'sitting in late 1900. The judgement of the court was in favour of Montgomeries shareholders. Jackson had to pay £975 for the 1,500 shares at 13s each that he was issued in the initial float but never paid up, the payment was to be paid within one month of 15th February 1901. PROV, VPRS 267/PO/1361, Victorian Supreme Court, Montgomeries Brewery vs. Jackson and others, Case 1040/1898 Montgomeries was Jackson's Waterloo. It didn't destroy him financially, but he must have felt that his reputation at least was damaged, perhaps permanently. The pressure on him may have contributed to his death less than three months later, at Eblana, on 9th May 1901.

At his death Jackson left assets of £17,483. His estate had to pay £3,515 to the shareholders of Montgomeries Brewing Company to settle the Supreme Court case. Due to Jackson being the only director with assets he had to carry the total settlement costs. The probate showed that at the time of his death Jackson held a range of stocks and shares, most notably in government bonds and debentures, in the Port Fairy Corporation (a land developer), in a number of gold mines including one in Queensland and another in Tasmania, with Dan White - the well-known coach building company - the Modern Permanent Building Society, the Herald & Weekly Times newspapers, the Hoffman Patent Steam Brickworks as well as the Buchanan Gordon Diving Dress company. PROV, VPRS 28/PO, Probate Thomas Joshua Jackson (Executors' Acc6unt), and PROV, VPRS 28/P2, Probate Thomas Joshua Jackson 1901 (Probate Jurisdiction),

Somewhat oddly, Jackson had few investments in beer. At the time of his death he only held shares in the leading malting company of Samuel Burston & Company; he had, of course, also invested in Montgomeries. He kept a phaeton and horses at the Hotel & Livery in Collins Street of James Garton, a long established hotelier (Garton was also a Director in Dan White's coach-making company). One of Jackson's last investments was in Buchanan Gordon Diving Dress Limited, floated on the Melbourne Stock Exchange in 1899. The product driving the float was an underwater diving suit which allowed the diver to safely reach 30 fathoms (about 50 metres), remain underwater for lengthy periods and even talk by telephone to the surface.

Overall, Jackson's share investments, despite the stressful debacle of Montgomeries Brewery (and even that paid well for many years), must have provided a reasonable income stream. However, by the time of his death many of his shares had little value, bringing in only around £1,500 at probate. Even Jackson's interest in 'new technology' stocks, as they would be called today, did not payoff for him - Montgomeries Brewery, Hoffmans Brickworks, some of the mine technology and even the Buchanan Gordon Diving Dress were highly innovative firms and products for their time. But at his death, Jackson's most valuable shares were the 661 he held in the Herald Standard [newspaper] Company - worth £1,090 at probate, followed by the 1,041 shares he held in the Great Extended Hustler Gold Company, worth £780.23. PRO V, VPRS 28/P2, Probate Thomas Joshua Jackson (Probate Jurisdiction)

Jackson was made secure financially, more than anything else, by his modest investment properties and of course his own home (altogether worth over £9,000), backed up by Government stocks, debentures, holding of two mortgages on Hawthorn properties and cash in the bank (worth over £7,500). It was this 'balanced portfolio' which allowed Jackson to overcome his debts and provide handsomely for his widow. Jackson also held a modest but wholly respectable investment property folio which included seven other houses which he rented out in Fitzroy, Carlton, Collingwood, South Yarra, East Melbourne and South Melbourne, plus some land in Moonee Ponds. PRO V, VPRS 28/P2, Probate Thomas Joshua Jackson (Probate Jurisdiction)

With the death of Thomas Jackson in 1901, Sarah Jackson remained at Eblana. In 1907, Sarah Jackson's son James Cavanagh also died, at the age of 45, leaving a widow, Ellen. James Cavanagh had apparently been a heavy drinker, contributing no doubt to the liver disease which killed him; he was also virtually 'broke'. At his death in 1907 his only assets consisted of 650 shares in the Northcote Brickworks worth £455, a £2 share in the Morwell Tennis Club (from his days in Gippsland), and £78 of assorted jewellery. Listed among his liabilities at probate was £16 advanced to him in 1907 by his mother a bleak testimony to Cavanagh's circumstances at the time. PROV, VPRS 28,106/363, Probate, James Henry Albert Cavanagh. Ellen Cavanagh married John Connell after the death of her first husband and continued to live at Eblana with Sarah Jackson, John Connell is Sarah's brother's son who later became famous as the owner of Connell's hotel in Elizabeth street and left a fourtune to both the Anglican church and the National Gallery on his death. Sarah's died on Christmas Day, 1924, aged 84. Sarah Jackson was buried with Thomas Jackson and her son James in Kew Cemetery.

What of Sarah Jackson's assets, including Eblana? In her Will, assets included an oil painting of Melbourne Cup winner Carbine (very possibly the Frederick Woodhouse Jr. oil on canvas painted in 1889 and now in the State Library of Victoria's collection); several thousand pounds in cash to relatives, friends and house-maid, donations to the Organ Fund of the Vestry of the Holy Trinity Church in Clarendon Street East Melbourne, the Queen Victoria Hospital; and the City Newsboys Society. The balance of her estate was divided into shares to be divided among the wider circle of Young and Connell relatives. PROV, VPRS 7591/P2, Will, Sarah Isabella Jackson 1920.

Altogether, at probate Sarah Jackson's personal assets consisting of personal effects, cash, debentures and shares realized assets of £25,918. Sarah held Commonwealth Government Treasury Bonds, and Debentures of the State Savings Bank, the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works, the Metropolitan Gas Company and the Victorian Government. She had shares in the Northcote Brick Company Limited and the Commercial Bank of Australia but the bulk in the Herald and Weekly Times Ltd. (these last realised £7,126 alone). In addition she held a similar mix of property to her late husband, which were all sold and brought in £11,000. PROV, VPRS 28/P3, Probate Jurisdiction Sarah Isabella Jackson 1925.

Less than a year later, in October 1925, Eblana was sold (described as a 'magnificent brick residence' in the auctioneer's flyer) to the Commonwealth of Australia, when it was used as the head office of the Post Master General; various owners followed. Cawthorne, Z., 'The House that Beer Built', Herald-Sun Weekend, 24th July 2004, p.11. These included by 1983, a subsidiary of Telecom Australia. Later that year, a National Trust survey described Eblana as a ' ... boom period render Italianate style terrace dwelling with a two storey colonnade and parapet over. The grand entry is approached by a flight of substantial bluestone steps ...' 'National Trust Survey', dated 26th July 1983, in the Fielding Collection.

In 1983, just over 100 years since it had been built and occupied by Thomas Jackson and his family, Eblana came up for auction once again. A real estate reporter wrote: ' ... The agents suggest the building would be ideal for offices or professional use, but also suggest, rather wistfully, that someone might want to live there.' In 1997, the neglected house was bought by entrepreneurs Peter and Nancy Fielding. The couple got to work to extensively restore Jackson's house, inside and out. Eblana today is a 'beautifully restored Victorian gem, in which antiques, reproduction pieces and classic elegance blend effortlessly', thanks to their generous and sensitive restoration.

Jackson lived through one of the most exciting periods of Melbourne's history. When he arrived just 14 years after the Colony was proclaimed, Melbourne was a very raw town. Bushrangers still held up travellers near the house signed as the Elsternwick Hotel after it had been built in 1854. Albert Lake as it is known now was a swamp and in 1856 the future Young and Jackson Hotel was a butcher's shop. From such beginnings, and with luck at the New Zealand gold fields, Jackson and Young slowly but surely built a highly successful hotel business together.

This brought Jackson opportunities to build his wealth, which he was able to do and it brought Jackson to Jolimont, where for 20 years his house reflected both his success and provided him and his family a magnificent home in which to reflect on his journey in life. It was a long way from Jackson's arrival in Victoria in 1852 as a young man with perhaps uncertain prospects. His home Eblana became an expression of his success in 'Marvellous Melbourne' - and a haven during the recession and unhappy failure of Montgomeries. Despite the disinterest and neglect of its many occupants since 1925, it is the story of Eblana which fittingly ends the narrative of Thomas Joshua Jackson, for it stands beautifully restored today. 130 years since it was built, Eblana stands today as Jackson's main legacy.

*It has since been established that the billiard room was built in 1898 for Thomas Jackson by G W (George Wilson) Dodd. In the building register it was described simply as an 'addition' but the 1899 rate books [Albert Ward ref no 804]refer to it as a billiard room.

[PROV. Building Register VPRS 9289/P0001/000006/[type] VH1. Mar 27 1898/Reg. No. 7204]

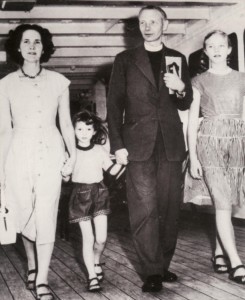

Louise and Robert Johnston 1909Mary Louise Friedrichs, known as Louise, was born in 1880. Her father had migrated to Victoria from Hanover, Germany, in 1860 hoping to teach the violin. Alas, such opportunities were in short supply and he became a wood carter, labourer and miner.

Louise and Robert Johnston 1909Mary Louise Friedrichs, known as Louise, was born in 1880. Her father had migrated to Victoria from Hanover, Germany, in 1860 hoping to teach the violin. Alas, such opportunities were in short supply and he became a wood carter, labourer and miner.

Louise and her three siblings grew up in a small miner’s cottage in Parker Street, Maldon. The family lived simply. Her mother, Mary Therese, born in Galway, may not have been able to read or write, but she could sing and she loved the Irish jig.

When young Louise left the local Catholic school she took a job as a scullery maid for Thomas Welton Stanford of Stanford House, Clarendon Street, East Melbourne (now the site of the Freemasons Hospital).

Louise’s grandmother, Maria Stanford, a hotel keeper, was born and married in Athlone, Roscommon, Ireland. She died in Ballarat three years before Louise was born. Two relatives of Louise, still living in Maldon, said their grandmother always said they were related to the same Thomas Welton Stanford for whom the young Louise worked, and indeed they thought that was how she got the job.

Thomas Welton Stanford, the brother of Leland, founder of Stanford University, arrived in Melbourne in the 1860’s with a shipment of kerosene lamps. So successful was this new light that on the first night of its demonstration in a shop window, the sidewalk was so blocked with spectators that a policeman had to be stationed in front to clear the way.

Stanford married his Canadian born wife, Minnie, in 1869. She died the following year. Stanford was distraught and his interest in Spiritualism was heightened with his home regularly playing host to meetings.

We are not sure when Louise commenced working as a scullery maid in East Melbourne, but in 1900 she sent a postcard to her brother from Stanford House wishing him a happy birthday. Miss Annie Cupit was Mr Stanford’s housekeeper and one day her friend Miss Johnston paid her a visit accompanied by her brother, Robert Alexander Johnston, a boot maker. This was the man Louise was to marry in 1909. Their one and only child, William Robert, was born in Lilydale in 1911.