NEWTON, Eileen Catherine Kearney

Eileen Catherine Kearney Newton (1889-1937)

Eileen Newton was associated with East Melbourne as a parishioner of St Peter's Church, Eastern Hill on Gisborne St. Born in 1889, she was brought up in Numurkah, before leaving the town and training as a nurse in Melbourne.

In 1917, she followed her older sister Dorothy into the Australian Army Nursing Service and served in India until 1919. She worked primarily at the Deccan War Hospital in Poona.

In 1920, Eileen married Eric Richmond Bartlett Cullen, an electrical engineer who had served in the AIF and the Royal Flying Corps in England. They moved to NSW and had two children. They returned to Victoria about 1933, Eric Cullen holding a senior position with Claude Neon Ltd.

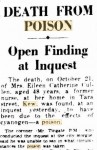

Eileen Cullen died of poisoning by prussic acid at her home in Kew on 21 October 1937. She was 48. The coroner returned an open finding on how and by whom the poison was administered. She was cremated at Springvale Cemetery, near Melbourne.

***

Before the War

Eileen Catherine Kearney Newton (1889–1937) was the younger of two daughters born to Henry Gildea Newton (1861–1915) and his wife, Isabella Jane (nee Kearney) (1862–1907).

Eileen’s father Henry had been born near Oakleigh, outside Melbourne, the son of a successful Irish immigrant, John Vigars Harvey Newton and Susan Liddiard. John Newton held large tracts of land around Oakleigh; John’s wife was the daughter of the vicar of his local parish, the Rev. W.W.W. Liddiard, himself a holder of land.

Eileen’s maternal grandfather, Arthur James Kearney, married Jane Campbell, a widow, in 1861. Life for the Kearney family was challenging. Arthur Kearney was declared bankrupt in 1869, the consequence of ‘being obliged to leave the civil service, owing to ill health; from becoming security for various parties, sickness in family and medical charges’ and his wife, Isabella’s mother, died in 1875 (Argus, 14.4.1869, p5; Illustrated Australian News for Home, 6.10.1875, p159). He subsequently moved to East Melbourne, remarried and established a second family in the 1880s – Isabella’s half siblings – who were baptised at St Peter’s Eastern Hill.

The Newton and Kearney families had characteristics in common. There was a public service connection, not only Arthur but also John Newton, sometime a local inspector of weights and measures, then Henry Newton, who was with the railways and then trade and customs (Victorian Government Gazette, 1882, 1884). The families were firmly Church of England, the Newton family at Holy Trinity Oakleigh and the Kearneys at St Peter’s Eastern Hill (where Eileen’s name appears on the Honor Board).

Henry Newton and Isabella Kearney married in 1886, and soon had two daughters, Dorothy Jane Louisa (b 1887), and Eileen Catherine Kearney (b1889). They lived on the recently sub-divided Emo Estate in Malvern, near Henry’s cousin, Hibbert Henry Gildea Newton, also a public servant. The cousins seemed to have shared business interests, travelling together to Launceston for example in 1890 (Argus, 3.2.1890, p4).

In 1895, Hibbert was declared insolvent. This may have prompted Henry, Isabella and their two daughters to move to Numurkah in central northern Victoria around the same time (Weekly Times, 10.8.1895, p35). Isabella and her brother Arthur already owned a drapery business in the town; they sold it in 1895 perhaps so Isabella could liquidate assets for her family (e.g. Argus, 23.11.95, p3). Numurkah had a population of around 1000 people in 1891, and was connected to Melbourne by the railway.

The Newton family, Henry, Isabella and their two young daughters Dorothy and Isabella were soon well-known in Nurmurkah and the surrounding districts. Isabella was an accomplished singer, pianist and artist with Melbourne training and recognition (Numurkah Leader, 11.6.1895). She took music pupils and trained them for higher examinations, but above all she quickly threw herself into the many entertainments, concerts and plays held in aid of worthy causes in and around the town. She also spoke at meetings in the district promoting the conservative Australian National Women’s League, and was an organiser for the League during Federal elections (e.g, Argus, 13.11.1913, p6). Henry Newton kept a lower profile, his activities other than sporting clubs uncertain, though he was for a time the local inspector of abattoirs and slaughterhouses (Victorian Police Gazette, 6 July 1911, p346). In 1900 he took on the role of secretary, caretaker and librarian of the Numurkah Institute, an organization with a history of poor management. The remuneration was £50, commission on fees, a cottage on the premises with fuel and light provided. He was chosen over 165 candidates, some with ‘library and other special fitness for the position’, his ‘energetic and popular wife’ being a decided asset. He made immediate improvements and was hailed as a successful appointment (Numurkah Leader, 9.3.1900, p4, 27.7.1900. p3).

The two Misses Newton, Dorothy and Eileen, were popular and admired figures as they grew up in the town. Like their mother, they acted and sang in various local entertainments, and worked for the local parish church. Dorothy’s singing talents were such that she matriculated at the Melbourne Conservatorium in 1905. The Numurkah citizenry held a benefit concert for her and raised the funds for her first year’s fees (Numurkah Leader, 24.11.1905, p2, 15.12.1905, p5).

The singing career did not eventuate, however, and after several years teaching piano back in Numurkah, Dorothy turned to nursing as a profession. Both she and Eileen left Numurkah for Melbourne (the loss of young people lamented by the local paper) in early 1911, training together for three years at the Children’s Hospital in Carlton.

During the War

Eileen’s sister Dorothy enlisted in the Australian Army Nursing Service in early 1915. She saw service in hospitals in Egypt and France, as well as in casualty clearing stations on the Western Front. She was promoted to sister and decorated with the Royal Red Cross (2nd Class) (Dorothy Jane Louisa Newton, Service Record [NAA]).

Eileen’s career was shorter and served completely in India. As the younger daughter, she was less free and independent than an older sister. Henry and Isabella had moved from Numurkah to Melbourne in 1913 (Argus, 13.11.1913, p6), and after completing her training she lived with them in Malvern. Her long-standing intention however was to enlist: when Henry died in 1915, the Numurkah Leader noted that one of his daughters (Dorothy) was at the front and that the other, ‘Miss Eileen is expected to follow shortly’ (Numurkah Leader, 13.8.1915, p8).

It was almost two years however before Eileen enlisted in the AANS (Eileen Newton, Service Record, [NAA]). She joined in June 1917, embarking a fortnight later for India with 60 other trained nurses mainly from Victoria. The journey from Melbourne to Bombay (now Mumbai) took a month.

Unlike her sister Dorothy who was by then serving in France, Eileen’s entire period of service was spent in India. India was the destination of 20% of the AANS who served but it was not a declared a theatre of war, which was a source of frustration to many who longed to be closer to the action. (For the AANS in India, see Ruth Rae, Reading between unwritten lines: Australian Army Nurses in India, https://www.awm.gov.au/journal/j36/nurses/; M. Barker, Nightingales in the Mud: The Digger Sisters of the Great War (1989)).

Eileen Newton’s service record provides little detail beyond the date and location of her posting. Immediately on arrival in Bombay on 30 July 1917, she was dispatched to the Deccan War Hospital near Poona, some 150 kms away. She appears to have spent the entire war there although she may also have nursed in one of the several British military hospitals in Bombay. She was later denied the Victory Medal, given to those who did serve in a theatre of war; to be eligible in India she needed to serve on the North West Frontier or on a hospital ship travelling between Mesopotamia (Iraq), German East Africa and Bombay.

Deccan War Hospital was located near a military camp and had been greatly expanded in 1917 to take 1000 beds. The matron and 50 or so nurses were Australian, the doctors and orderlies were English. The patients were casualties from the fighting between the British and Turks in Mesopotamia (Iraq) brought by hospital ship to India. They were suffering from battle wounds and a range of illnesses including malaria, dysentery, cholera and the effects of severe heat stroke (Barker, Nightingales in the Mud, p76).

The climate (summer, monsoon and winter) was palatable rather than extreme, though some found it trying. Mosquitoes were rife, as was malaria. Eileen succumbed to malaria a fortnight after she arrived. It may have become recurrent but she declared she had had no attacks ‘lately’ when she returned to Australia in early 1919.

Photographs of the hospital (Australasian, 2.6.1917) show a substantial building with the new tented wards which had brought the hospital’s capacity to 1000 beds in mid 1917. Newton was part of the expanded nursing establishment. The photographs also showed nurses enjoying the grounds of the residence of the Governor of Bombay, which they were permitted to use for recreation.

Florence Grylls from Bendigo nursed at the hospital in mid 1917, and described conditions there (Bendigonian, 1.11.1917, p5):

We all have to use mosquito nets, and never sleep without them. Poona is considered a good summer climate. The Governor is in residence in the town, three miles from here … We have a galvanized iron room, with wide tiled roof and verandah, back and front. There is rush matting on the floor, as the snakes can’t crawl on it … There is tennis, golf and boating in Poona, three miles away.

At least one other nurse from Eileen’s parish of St Peter’s Eastern Hill, Katie Brooke, served at the hospital at the same time.

Eileen would have been eligible for several periods of leave, which she may have taken in England and where, if their leave coincided, she may have met up with her sister Dorothy.

After the War

Eileen returned to Australia in March 1919. Like many others in the AANS, she continued to nurse sick and wounded soldiers, working at 11 Australian General Hospital, Caulfield for 12 months after her return. Some of that time she spent trying to secure her entitlements as her pay book had been sent to England (Newton, Service Record).

In 1920, Eileen Newton married Edgar Richmond Cullen in St Paul’s Cathedral, Melbourne. The marriage notice in the press referred to Edgar’s service (‘late AIF’) but not Eileen’s (Argus, 4.9.1920, p13). Cullen was an electrical engineer from NSW, and the couple moved to Sydney soon after.

Edgar Cullen served first as a private in the AIF (1915 –17) in Egypt and France, then transferred to the Royal Flying Corps as an aircraft mechanic until his demobilization (1917–19). Cullen had a chequered military career in both services (Edgar Richmond Cullen, Service Record). He was listed as a deserter soon after landing in Eqypt in March 1916, then hospitalised with gonorrhea in France in late 1916/early 1917. It was the first of several hospitalisations for VD between 1916 and 1919, totaling 141 days in all, his pay docked in accordance with policy. All but the first hospitalisations were in England, where he was stationed as an aircraft mechanic at various airfields. He may have met Eileen while she was in England on leave from India although her sparse service record provides no clue.

Cullen may very well have kept his health issues completely to himself. He and Eileen had children in NSW, then moved to Victoria about 1933 where he took up a senior position with Claude Neon Pty Ltd. The couple’s name appeared from time to time in newspaper social notes.

In October 1937, Eileen Cullen died at her home in Kew, the result of poisoning. The coroner returned an open finding on how and by whom the poison was administered, but the inquest was reported in the press (Argus, 1.12.1937, p6). Her husband attested to her care with poisons in the home, and her sister and brother to her happy family life. Her body was cremated less than two days after her death. In 1939, Edgar Cullen remarried in a quiet church service, his wife Marjorie Townley an employee in the company and well known for her charity work for the blind. They had at least one child.

Eileen Cullen was cremated at Springvale near Melbourne.

Eileen Newton (Cullen) is commemorated with parishioners who served in World War 1 on the honour board of St Peter’s Church, Eastern Hill. There is no other evidence of her connection with the parish. She may have attended the church or its St Barnabas Guild for Nurses when training at the Children’s Hospital (though Dorothy is not listed) or she may have worked in one of the numerous hospitals in the vicinity prior to her enlistment and embarkation.

Janet Scarfe

Adjunct Research Associate, Monash

2 September 2016