Kalingra: a story of firsts

East Melbourne is rightfully known for its Victorian era streetscapes. However, between the wars it went through a period of re-development resulting in a scattering of buildings that are markedly different in style.

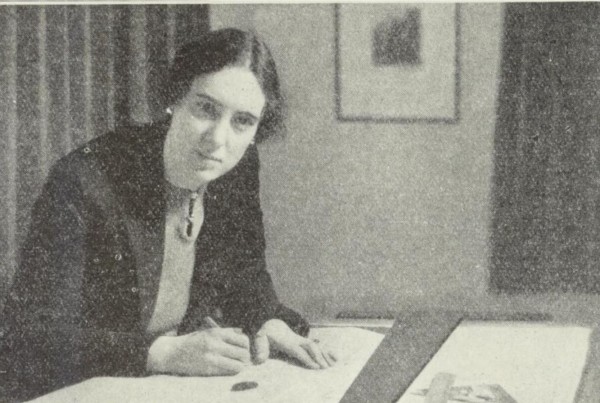

One of these is a small block of six flats at 109 George Street. It was originally called Kalingra but the lettering on the gatepost has been damaged and it is now known as Kalingi. It is notable for having as its designer, Edith Ingpen, the first woman to gain an architecture degree from the University of Melbourne, passing her final exams in 1933.

Before completing her degree Edith had begun work in the practice of Harold Desbrowe-Annear, the leading architect of his generation. Desbrowe-Annear died soon after, in June 1933, and Edith took the plunge and set up on her own.

Edith had graduated at an opportune time: Melbourne was beginning to emerge from the devastation of the Great Depression and work for architects was on the rise. Even so, such a large commission as the East Melbourne flats to be given to a brand-new practitioner is surprising. It was, perhaps, a matter of being in the right place at the right time.

The Ingpen family, consisting of Walter Cecil Ingpen, his wife Emma Louisa and Edith herself had, in 1931, moved into a flat at Thorlinda, 108 Wellington Parade, East Melbourne, immediately behind 109 George Street. Also living at this address were William George Pamphilon and his wife, Marjorie Lillian. It was William’s brother, Henry Thomas Pamphilon, a well-known bookmaker, who had bought the old house at 109 with the intention of knocking it down and building the new flats. Introductions were no doubt made.

This was Edith’s first job and also a first for East Melbourne in being the earliest building designed in the Moderne style. She lost no time in getting to work on the project, lodging plans with Council in August 1933.

A feature article about Edith and her work in The Age of 24 July 1937 highly praised the result, commenting that the architect was required ‘to design a building sufficiently imposing and dignified with only [a] meagre 28 feet [frontage] to work on’ and continued that ‘the light-toned color scheme and horizontal windows and balconies give the effect of added breadth’.

On completion of the building William and Marjorie Pamphilon moved into the flat on the second level overlooking George Street. Henry let them have it rent free as William was not well, suffering severe shell shock in WW1. In return William acted as caretaker for the building until his death in 1952. Marjorie remained there until the early 1970s when she moved into a nursing home. Henry had died in 1940 but the property remained in his estate at least until Marjorie moved out.

Henry appears to have been a kind and generous man, and that is perhaps part of his reason for giving a kick start to the career of an unknown architect, plus of course his ability to judge a good bet.

Edith, meanwhile, continued her practice, specialising in residential buildings, until the outbreak of WW2. Again, opportunities for architects dried up and Edith joined the Victorian Public Works Department where, as a woman, she was severely handicapped in terms of pay and promotion. Finally fed-up she resigned in 1965 and moved to Bristol, England to follow her long-held ambition to be a painter. She died in England in 2006.

Kalingra remains Edith’s major work and, like its contemporaries, it sits amongst its older neighbours quite peacefully, unlike its many times larger and more strident modern counterparts.

This article first appeared in the Inner City News of July 2022